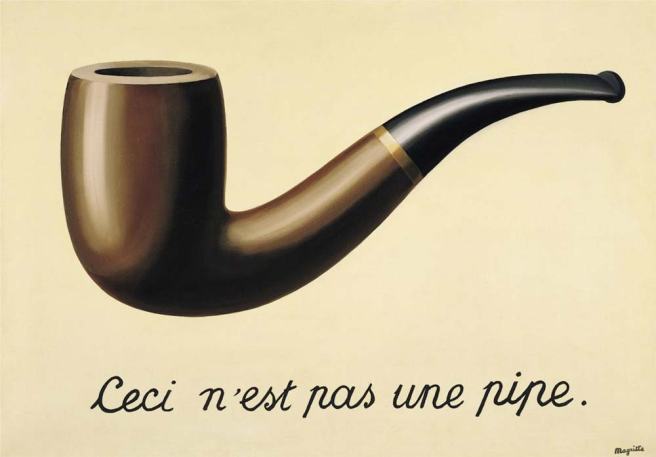

I used to have this postcard portrait of Marcel Duchamp stuck on my car’s dashboard. This image is both ironic and a fitting sentiment of the artist. Perhaps whoever made it also was trying to reference Magritte’s The Treachery of Images:

Duchamp never wanted to be a role model. The art world filled him with ambivalence. After he failed by his own admission at “fine” painting, all he wanted to do was pose questions and experimentally answer those questions with punning riddles in the guise of paintings, sculptures, films, iconologies for existent and non-existent works, writings, and music. And play chess.

I’ve had very few art experiences in life where a transformation of my world occurred. Encountering Duchamp’s readymades was one of them, especially his criterion for choosing them: “visual (or aesthetic) indifference.” He chose them precisely because he’d never considered them in any aesthetic terms. An object you’ve lived with your whole life, ignored, invisible, suddenly announces its presence as a form. Nothing has changed. Everything has changed. You’ve just “enshrined” the object but just as it begins to glow with significance it fades once again into the background, inert. It’s lost, but you never possessed it in that way in the first place; you were indifferent. It’s free to reappear in its own time.[1]

With this oscillating “frame” of significance Duchamp anticipated (perhaps created?) the cultural world we now live in; the repurposing of objects has become known as appropriation or the mash-up.

At some point early on he discovered that the norms of the art world were more important than, and actually preceded, the physical objects which they instantiated. To make a game out of aesthetic choices, and art a realm of “possible worlds” an artist could by choice inhabit or change, was revealed. Duchamp just showed us that we play hide and seek with our own and society’s values, our artistic success depending on a host of occult and marginalized factors.

Duchamp couldn’t be a role model because he was a singularity. He was his own “factory” long before Warhol could envision a Factory to produce the “aura” (aurea=gold) of art. Duchamp tried via his readymades to break the barrier between the mundane and the sacred, the haute monde of art and the mass produced culture, decades before Warhol; Warhol is unthinkable without Duchamp—as well as hundreds of other famous artists. He’s arguably the most important artist of the 20th century.

Duchamp was attracted to alchemical texts and imagery because they were the product of symbolic codes between solitary practitioners. He could understand his own position vis a vis society and the art world through the lens of the consummate outsider/insider, an inhabitant of the liminal space—the trickster. Hermes-Mercury, the trickster-messenger figure, was also the patron of magic and alchemy. To the public, alchemical texts made no sense, just as they were designed to. Their arcane vocabularies, neologisms, and often-violent imagery were meant to protect the sacred truths against profane eyes (as well as confuse the authorities who might detect a whiff of necromancy).

Many of the Dadaists and Surrealists were interested in alchemical jargon and images, but only because it satisfied their taste for apparent irrationality; they understood them only as hallucinations or automatisms brought on by the alchemists’ chemical experiments or drug ingestion.

We have since learned much more about the history, methods, codes, and goals of alchemy. At its most basic you might say alchemy is the transformation, by natural yet hidden means, of elements that make up everything known in the universe. Traditional alchemy concerned obtaining the prima materia, the unchanging essence that underlies all elements, and using it to transform metals into “nobler” forms. All of the procedures had counterparts in the psyche of the practitioner, and, some say, originate and end there.

The Philosopher’s Stone is, of course, most associated in the popular mind with the turning of lesser metals into gold. We could easily interpret the concept and execution of a readymade as an attempt at inducing mental and emotional alchemy on the spectator—but only those who might already be primed to understand such a thing.[2] At some point in 1912-13 Duchamp claimed a retreat from the plastic arts and denigrated them as retinal art: “retinocentric,” we might now say. We could expand this criticism to include time and notation as superfluous in music, as John Cage eventually did, and typography of linear words and their significations, as e e cummings, say, did in poetry—and center art in the mind. The perception makes the thing intelligible and special to the viewer, who co-creates the art experience. Duchamp in a sense democratized the art experience to be whatever moved one to experience it as such.

Obviously this tremendously undermined the social values of the art world and its tendency (at the turn of the 20th century) towards increasing commodification.

Duchamp was an atheist, but did he hold any spiritual values? He certainly denigrated art’s power as a surrogate for religious sentiment…At some point, with material science replacing the qualitative values of religions into the quantitative values of the physicist and technocrat in society, the plastic arts came into their own as a source of spirituality. Eliphas Levi’s occult writings, the Spiritualist movement, and Blavatsky’s Theosophy inspired a counter-current to the quantitative mindset that was indoctrinating millions of minds. Along with these came waves of art movements: Neo-Classicism (Academic art), Impressionism, Symbolism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Orphism, Die Brucke, and pure abstraction (the Blaue Reiter movement, with Theosophist Kandinsky as its proponent). The manifesto-mills were at full capacity.

Duchamp, however, shared in the burgeoning technological fascination and the cult of automation. He was enamored with the machine’s anti-aesthetic, it’s pure functionality, and viewed them as allegories for social relations, sex, and certain modes of human consciousness, a multi-variant mirror that yet was not “reductionist” as we’ve come to know that term. His stance was more like a prefiguring of Marshall McLuhan’s view of technology as extensions of the human form, senses, and capabilities. For Duchamp high technology was more material to be worked with, to other ends than the pragmatic—to engage the “useless beauty” of the artistic gesture. Here was yet another reversal of values.

Then came the Great War. In the wake of this catastrophe, “civilized” values became suspect to the art world in the political oasis of Zurich. Freud’s ideas of the unconscious thanatos drive in the European/American psyche spread and found expression in the Dadaist’s shocking destruction/deconstruction/dismissal of “bourgeois” aesthetic standards, a social counterpart to the deaths of the war and1918 flu pandemic. The techniques associated with Spiritualism (trance states, automatism in writing/poetry-making and painting and drawing) and utilizing chance became working procedures for artists via the Dadaists.

Duchamp never formally associated himself with the Dada movement; he’s rather considered via the readymades their “patron saint” or an isolated inspiration. His conceptions of the rationale for the readymades changed over the decades; he was never certain, in retrospect, what impelled him to make such a move in the first place. But with the readymades, a transformation of consciousness perfectly in sync with the alchemists’ project was made possible. Collage had been used in Picasso’s and Braque’s Synthetic Cubist experiments, and by 1917 the Dadaists were cutting up all sorts of things into collage. But to hack the art world by recontexualizing an everyday object, unaltered, whether a coat rack or bottle rack or tilted urinal, was unthinkable until Duchamp did it. Puzzlement and derision followed Fountain (1917), now considered the most important work of 20th Century art.

He did many variations of readymades. Some, like Pharmacie, were “rectifications:”

This is a simple store-bought painting, “completed” or “redeemed” by the addition of two dots, one red and one green—the colors associated with drug stores in France. What he did was reverse the arrow of signification in Walter Benjamin’s “age of mechanical reproduction”: he took a “pre-reproduced” object and exhibited it as a unique object. He reversed the value of the negligibly valueless. But only a small number; the majority of his readymades were “rectified” objects or altered to fit his idiosyncratic personal mythology. Other rectified readymades were deliberately provocative, like the goateed Mona Lisa, LHOOQ:

In French, this title phonetically sounds like the phrase “she’s got a hot ass.” Besides repurposing the trivial, Duchamp’s other long-time exploration was with gendered identity. His alter ego Rrose Selavy (eros, c’est la vie—a bad pun, indeed!) appears on several works. Here’s his Belle Haleine/Eau de Voilette (1921), a title, via the transposed letter V for T, apparently meaning “Beautiful Breath of the Veil Water”:

It’s unfortunate, but there seems to be a rule that both modern and (post)modern art’s meaning to the audience and art history, as measured in the amount of ink spilled in explaining it, is oft times in inverse proportion to the amount of “craft/skill/representational talent” the given work being explained actually displays. This thought occurred to me while reading Clement Greenberg’s and Harold Rosenberg’s defenses of Abstract Expressionism—and a similar thought formed the basis of Tom Wolfe’s notorious screed The Painted Word.

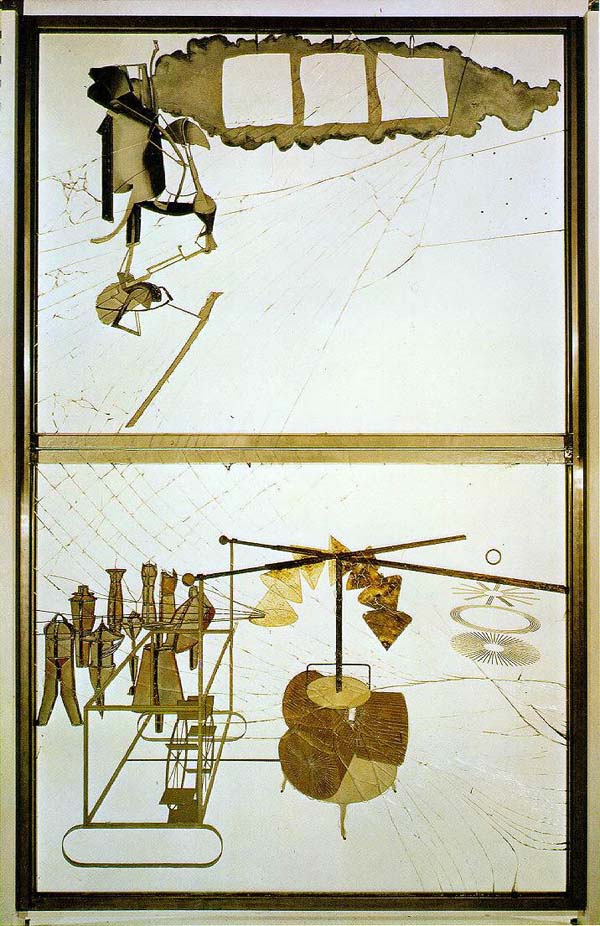

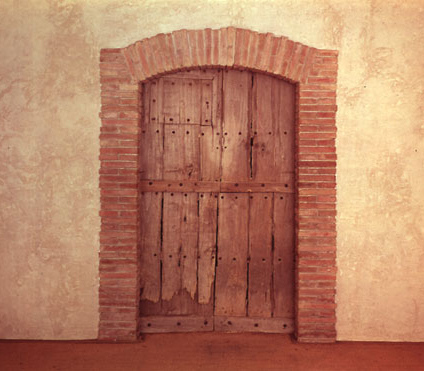

With Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, or The Large Glass, we have this tendency to explanation brought to its absurd extreme, and all the hermeneutics done by the artist himself in the subsequently published Green Box, a collection of all his notes, diagrams, and explanations of the iconology of the piece. So we have an artist imagining the context, history, function, and critique for his own piece in advance of and alongside its creation, a dialogue with his unconscious. He was thus ahead of his own posterity in creating his own mythology…The same occurred when the Philadelphia Museum of Art revealed Duchamp’s final work, Etant Donnes: la chute d’eau 2. La gaz d’eclairage (Given: 1. The Waterfall 2. The Illuminating Gas) which he’d secretly spent decades on and seems at once a condemnation of the museum-goer/haute monde critic/collector as voyeur, and a literal wooden “façade” behind which a “truth” is to be discovered.

This is its “aesthetically indifferent” facade.

Get up close and personal, gaze into a certain crack in this mask, and hello!:

Inside

——–

Many thousands of artists can claim Duchamp as a direct inspiration (or those inspired by him as a secondary muse). Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg, and the other quasi-Pop artists of the late 1950s and 1960s incorporated found-object (readymade) elements in their work. Collaborations between Rauschenberg, choreographer Merce Cunningham, and John Cage resulted in multi-media events that prefigured the late 60s Happenings. Some of Warhol’s films elevated the mundaneness of the “retinal” to absurdity, yet they prefigured the video painting-installations of Bill Viola. Stripping art of its need for embodiment led to the jokes of Piero Manzoni and Yves Klein, the Arte Povera movement, the whimsical “experience recipes” of Yoko Ono and Fluxus, and the artist’s ego dissolution into actions like Joseph Beuys’s. Individuals from the “postmodern” dance world, influenced by Duchamp via Cunningham and Cage, came together with Robert Wilson’s unique theatrical visions to produce tremendous operas that almost defy rational explication. Out of the Sixties’ Happenings and theater such as Wilson’s came the performance art of the 1980s, embodied most successfully in the multimedia presence of Laurie Anderson.

But this latter movement produced very few memorably shocking events (comparable to Fountain) that erased further the boundaries Duchamp had begun to; those had been rehearsed and “perfected” in performances during the free-for-all 1960s and 70s, like Chris Burden’s Shoot, Ono’s Cut Piece, Shigeko Kubota’s Vagina Painting, or the multimedia conceptual works of Sophie Calle and Genesis P-Orridge.

When we talk about contemporary international art, which names come up? Tracey Emin? Banksy? Jeff Koons? Damien Hirst? Christo? These persons are more like rock stars. Damien Hirst gets pounded all around for his faux-whimsy and creative bankruptcy and is perennially sued for plagiarism. Emin has coasted on the notoriety of one Biennale piece for quite a while. At a more “normal” level of “craft” we have Gerhard Richter, Matthew Barney, Anish Kapoor, Andy Goldsworthy,

[1] This recalls a story the composer John Cage, a Duchamp disciple and friend, once told about visiting a woman friend and having a few drinks while some strange music played from her stereo speakers. He enquired what it was and she replied, “you can’t be serious?!” It was a recording of his music, probably one of his star-map derived scores that were meant to mutate with each performance; the scores had come from transparencies laid across star clusters that Cage used the I Ching to determine which would be notes and which would be tone-clusters. The pianist-interpreter would read these as notes. Cage wanted to create pieces that were free from human ego as possible, for them to become a part of the world of sounds as sounds spontaneously appear to us. For him to unexpectedly encounter in the world the product of a “recipe” he’d devised must have delighted him.

[2] A person’s opinion of Duchamp’s readymades—whether they are brilliant ideas that expand one’s conception of art, or a bad (and poorly executed) joke—largely determines how one views many of the 20th century’s art movements (such as Dada, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, art brut, arte povera, Fluxus, etc.). The irony is, Duchamp would probably disavow the former and mildly agree with the latter!